Monthly Archives: April 2015

Short Reviews – The Star Eel, Robert F. Young

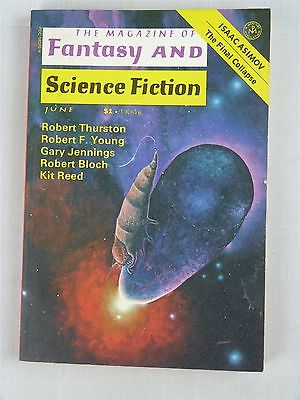

This was the cover story for the June 1977 issue of the Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction. It’s an okay-ish cover for an okay-ish story.

The Star Eel is a story with a lot of interesting ideas that are marred a bit by sci-fi cheese and a lot by half-hearted storytelling. Back in 1977, one could have a character named “Starfinder” and not be met with muffled snorts of laughter that eventually burst into guffaws, but really that’s the only part of this story that you can say didn’t age well. The rest is on the story itself. Why do I say half-hearted? Because of all of the lazy twists Young uses to extricate himself when he’s written himself into corners. Things work out simply because he’s got to get to the end of the story somehow to mail it off to Fantasy and Science Fiction. My reaction was pretty much the opposite of the Jennings story; everything was there to make me want to like this story but it just never quite came together.

The story’s premise is that the main character is the lone pilot/captain of a giant time-travelling Space Whale that gets attacked by a parasitic Star Eel. In this universe, Space Whales are hunted and their brains burned out by “Jonahs” because it’s easier to kill and gut one and fill it with space ship stuff than to build a space ship of equal tonnage. The same is also the case for Star Eels. Anyway, Starfinder’s Whale was unique in that it was double ganglioned, so Starfinder made a deal with the Whale that he would ‘save’ it by sparing its second ganglion and the whale would take him anywhere he wanted to go.

It turns out that Starfinder’s attacker is another intelligent ship that has been “liberated” by a little girl. Starfinder tries to convince the girl to detach the Star Eel, then unsuccessfully tries to trick the girl so that he can manually force the Eel to detach, and ultimately begs for the life of his Space Whale. The girl orders the Star Eel to stand down, but by now the Space Whale has lost it, isn’t going to listen to Starfinder or the promise he made to the girl that nothing bad would happen, and totally goes berserk on the Star Eel. Little girl bursts into tears as gobs of her space friend drift into deep space. Afterwards, the Whale feels really bad about what it did and promises to be the little girl’s friend so she’ll stop crying.

As a stand-alone, this was kind of a bad story. The concept of the living ships was cool, and some of the discussion on the relationships between ships and their pilots when ships are living things, but as a whole, the story was a disappointment. Starfinder was kind of a lame-o who screwed up in his ‘heroic’ attempt and only really got out of his predicament by grovelling to a 12 year old girl. I know it makes me a monster, but he would’ve been a more interesting/compelling character if he laughed in her face, all “Space Whale 1, Star Eel 0!” At least then you could be all “Wow, what a bastard!” and have a genuinely emotional response to one of the characters. The Space Whale’s ‘let’s all be friends’ seemed like too much of an easy-out for the story; Young didn’t know how to deal with the crying 12 year old any more than Starfinder did. The Star Eel might work if it were actually the first chapter of a longer story that better fleshed out the ideas and the characters, provided it doesn’t go into Piers Anthony territory. Otherwise it would be better rewritten as a pilot for a sci-fi reimagining of “The Misadventures of Flapjack”.

“Bubby’s sorry she killed your Star Eel, Flapjack. C’mere, n give Bubby a hug.”

Feminists Present Prestigious “Trailblazing” Award to Violent Abusive Narcisist

As a child, I watched her brutally and savagely beat her co-workers when she did not get her way or perceived any slight.

She would frequently force herself aggressively on men and violently attack them if they rebuffed her advances. This often included her seemingly reluctant significant other, who appeared to stay with her more out of fear of reprisal than love.

She was always insistent upon being the center of attention, often times to the detriment of both male and female colleagues. When she could not get her way by normal means of persuasion, she would rely on threats of physical harm.

Therefore it is shocking and outrageous that the Sackler Center for Feminist Art has chosen this year to honor Miss Piggy as a gender trailblazer!

Relax, folks, it’s only humor. Too bad Frank Oz isn’t still alive to accept the award on behalf of women everywhere.

Music – Umbra Vitae, Please Kill Me

Short Reviews – Not With a Bang But a Bleep, Gary Jennings

Another story featured in the July June 1977 issue of the Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction.

Mixing religious satire with science fiction is always an iffy prospect. There were times I wanted to be annoyed with the out and out silliness of Gary Jennings’ story and his refugee from Mad-Magazine protagonist, but I can’t tell you how many times it made me laugh out loud.

The premise is ridiculous: thought moves faster than the speed of light, so NASA decides to test this by strapping a “SoPrim (Southern Primitive) Protestant” minister to a wall in a rocketship. He accidentally prays them straight past Mars and into heaven.

The narrative is the minister compiling his report on the matter, explaining the full situation to whomever ends up debriefing them. The “Bleep” in the title refers not to any sort of computer or robot but the minister’s penchant to censor the speech of those around him in his official report.

He recalls how he was approached for the mission, the near miss with Mars, going off course and straight into a black hole in the middle of the Horsehead Nebula, and their strange encounter with a multiversal heaven created by a quasi-gnostic God, a tour of which is given by THE Dr. Livingston.

The snark and silliness that would otherwise be insurmountably aggravating had it been poorly executed is forgiven in no small part because of just how funny Jennings’ prose is.

“But the ravens brought Elijah bread and flesh. The Book of Kings says so. That one brought you a matzo and a worm!”

“Well, what other sort of bread would a good Tishbite Jew like Elijah consent to eat? And what other kind of flesh would a raven know?”

and

“Won’t I have Chaplain duties besides?”

“I daresay the rest of the crew will be too busy to require much spiritual counciling. And we know from the Viking robots that you won’t have to baptize or bury any Martians.”

are a couple of my favorites, as well as a series of out-of-context Bible verses used as thought-navigation while the crew scrambles and panics around the protagonist too long to really include in excerpt here. You certainly wouldn’t want your telekinetic navigator meditating on thoughts of “All we like sheep have gone astray” and “These are wandering stars, to whom is reserved the blackness of darkness forever”.

I’m kind of surprised that Mel Brooks never made an adaptation of this, simply rewriting the minister as a rabbi. The thing would make a great radio play.

Of interest to this year’s Hugo readers, the space ship is the Corrigan. That name keeps coming up EVERYWHERE.

I’ma let you finish, Salon.com…

…but this is the most insightful thing that’s been said about the Baltimore riots.

Bar-Lev Conclusion

The game of Bar-Lev that my dad and I had been playing wrapped up last week. I managed to plug the hole in Syria and keep the pressure up in Egypt enough to prevent an Israeli comeback.

We could’ve drawn it out a few more turns, but there was no real chance for Israel to turn things around on either front.

One of the strange things about the morale break rules that is unlike any other war game I’ve played is how it boosts attack values but doesn’t necessarily do anything else. In most games I’ve played, when a side’s morale breaks, it usually does all sorts of things like negating zones of control, reducing attack values, prevents or reduces chances to rally broken troops, incurs overrun rules, etc. In Bar-Lev, once a side is broken, all attacks against units from that side receive a bonus of 1. To give you an idea of what that means, a 1-2 attack goes from a 17% chance of success to a 34% chance of success and a 1-1 attack goes from 34% to 50% chance of success. Note that those are already better combat odds than most board games give you on attack (partly because rather than adjudicating combat on a single table with one roll, both sides get to roll to see if they inflict casualties). So, rather than the game slowing down when one or both sides’ morale breaks, it becomes a bloodbath.

My numerical superiority in both theaters allowed me to continue throwing troops against the Israeli remnants; for every regiment of infantry or tanks blown away by Israeli artillery, there were more to take their place and press the assault. Once I managed to neutralize a unit or two with artillery and airstrikes of my own, I was able to move through ZOC to knock out the surviving artillery.

Of note, the Syrian Air Force was almost completely destroyed. I think that the mistake my dad made was concentrating his fighter sweeps in singular theaters. The Israeli fighter planes are far superior to the Arabs; with about half as many planes running missions, there is a 100% chance that at least 1 Arab plane will be shot down, while generally, even if the Arabs run all of their planes, they can never quite get sure thing kills the way the Israeli Air force does. We plan on playing again, switching sides, and I’m going to test this – after a few days, the attrition on the Egyptian and Syrian air forces will give me the dominance I’d need to run heli-attacks (which my dad never managed, because he could never get the needed +50% air superiority needed until the war was already lost). Unless I’m REALLY unlucky, if I split my air force consistently, I’m looking at around 3-1 or even 4-1 rate of air combat casualties.

We’ll see!

Coming soon, more reviews of old SF stories.

Music – Theatres des Vampires, Woods of Valacchia

Short Reviews – Kent Cigarettes

I’d never seen nor heard of Kent Cigarettes before, though that probably has more to do with being a non-smoker than anything else.

The only ‘nice’ paper stock in the entire magazine is a double-sided full color heavystock gloss (I’m not going to try to guess the weight) advert for Kent Golden Light and Kent Golden Light Menthol Cigarettes touting them as having the lowest tar of all leading brands.

By 1977, Kent cigarettes had gone for two decades without using blue asbestos in their filters and were also being used as currency in Romania.

I’m pretty sure all 3 issues I have feature Kent cigarettes as their primary non-publisher sponsor. I’m not saying that Kent was bankrolling the entire Magazine of Fantasy and Science-Fiction operation, but given that their ads are on nicer paper than the cover binding, it makes me wonder!

Other ads in the June 77 issue include an offer for framable quality posters of past covers, a few various offers direct from Mercury Press (the magazine’s publisher), including a T-shirt ad, and a membership offer on the back cover from the Science Fiction Book Club.

Short Review – Books, Algis Budrys

This article from the June 1977 issue of The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, along with Baird Searles’ “Films: Jolly Juvenalia on the Silver Screen (which I will write about in the next post), gave me a brief glimpse into the origin of the “Fan Writer” category; in the ancient days before everyone could blog about what they thought about this or that book or movie or tv show, the lucky few got short articles published in the serial zines telling us what they thought about what to read and watch. These posts won’t quite be reviews, though; I feel weird reviewing reviews, so instead I’ll just try to summarize them & highlight a few choice bits that convey their feel.

Budrys takes on “Jules Verne, a Biography” by Jean Jules-Verne, “The Book of Virgil Finlay” compiled by Gerry de la Ree, “Lone Star Universe” edited by Proctor & Utley, and “More Women of Wonder” edited by Pamela Sargent.

Budrys points out that despite our constant exposure to Verne and his influence on Science fiction, we know him mostly through film and tv adaptations, comics and childrens’ books rather than his actual work, which he describes as “usually awkward and damned dull” even “in the good translations”. Thinking back, I’ve only read the childrens classics versions of the various Verne books, and those decades ago, so I don’t feel I can comment on his statement. His general summation of Jean Jules-Verne’s book is that it’s charming though lacking in decent literary judgement, lending to its warm charitability towards even mediocre work. “God grant me a grandson…like [Jean Jules-Vern].”

“It has always been true that there were three or four who could out-illustrate Finlay at any given time, just as it has always been true that SF always has had better artists than it deserved, balanced by an equal number of people who should have remained luncheonette sign painters.” I actually had to look up some Virgil Finlay. Yowzah! Here Budrys writes less a review of the compilation and more a eulogy for a beloved artist who never quite got the credit (or at least the compensation) he deserved during his lifetime. “…the man was grievously misplaced among us, and terribly unrewarded. Yet, despite our help, he brought most of it on himself.”

Budrys seems wary of the need for ‘regional’ compilations, in this case one meant to capture “some particular geist which is uniquely Texan” in Sci-fi. “There are some things in here because you are going to meet these people, or their reputations, at the next regional con, and how could you explain the omission?” Politics are everywhere always, aren’t they? He has praise for a number of the stories, concluding “it does change your image of Texas”, though he never leaves me 100% sure he meant it as a good thing.

Finally, Budrys has favorable words for the stories in More Women of Wonder, though it’s his take on Sargent’s introductory essay that makes up the meat of his comments, some of which sound as though they could’ve been blogged just yesterday. “I think when fiction attempts to teach deliberately, it runs serious dangers of distorting life, and is in certain peril of not being fiction at all, but something else. ‘Literature has the tacit aim of improving us,’ Sargent goes on to say, and I say ‘Who says?’ … If you select out all the SF which fits [Sargent’s] definition and call it ‘serious science fiction,’ then by definition serious science fiction is that which questions, etc., and anything which does not have an overt aim at questioning past values or posting future alternatives – ie, does not have a dialectical thrust – is not ‘serious.’ And we all know that not to be serious is not to be of worth.”